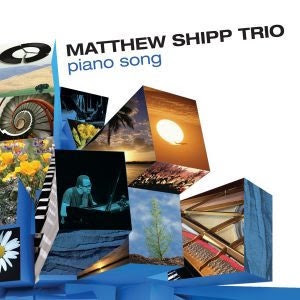

In this small record shop I found out, in effect, for half their price these three CDS of free jazz and contemporary music. Two are double albums. As I discovered at home, listening to them, they were worth the price and the time I spent listening to them. The first album is a piano trio by an old acquaintance of this blog: pianist Matthew Shipp, in a collaboration with long time collaborator bassist Michael Bisio and drummer Norman Taylor Baker. The CD is titled Piano Song and it was released by Shipp’s label Thirsty Ear in 2017. It is the most recent release of the three I’ll write about in this post.

A little disappointed by one of the last outputs by Shipp in a quartet comprising Paul Dunmall, Gereald Cleaver and Joe Morris (here is the review) because of its predictability, I find this other trio album, instead, exquisite, intense, fresh and innovative. Matthew Shipp is, above all, a spiritual musician. The world became aware of him thanks to his work with the great saxophonist David S. Ware, devoted to free jazz and to Ganesh, and thanks to his big open chords and great melodic approach to piano, along with bassist William Parker and many drummers – the one I loved the most was Susie Ibarra – he renowned the great tradition of energy playing, in line with the historical quartet of John Coltrane for the Impulse! label.

That’s why the second, double album in this multiple review article is so important. It is an album by another great pianist – one of the greatest in jazz history to tell you the truth: ‘Muhal’ Richard Abrams, founder of the Association for the Advancement of the Creative Musicians I mentioned in a series of articles about the Art Ensemble of Chicago few years ago. Abrams is a versatile musician: his many records spans through Contemporary Music and Jazz, and if Sightsong, a beautiful album duo with bassist Malachi Favors from the AEoC was a melodic and melancholic output, this other release, titled Sound Dance and issued by PI Recordings in 2011 is dominated by an impressionistic, pointillistic and vibrating style.

The first disc of the set is a duo with saxophonist Fred Anderson, the second features instead George E. Lewis at both trombone and electronics. If during the concert with Anderson it is more clear who is leading and who is accompanying, the second set is the most intriguing for how both the trombone and the electronics are mixing with the piano notes. The drive becomes less evident, almost hidden, and this sensation of uncertainty comes to the listener without a decisive solution, even if the music is capturing the attention with his beauty and peculiarities. After all what we’re listening to is a dialogue, and, as it happens when you speak to another person, sometimes your words are driven more by the person you’re interacting to than by your ideas and concepts. Call it interaction, or relationship: but it’s the same with music and it’s interesting to hear such a thing happening during a performance.

The first disk, instead, features three compositions for large ensemble – one, Jalons, directed by Pierre Boulez driving his Ensemble Intercontemporain, plus Keren, for trombone, and Nomos Alpha for cello. These are all compositions by the late Xenakis, who let apart his stochastic approach to music – you can read my monography about the composer in this blog – but who was always curious about pushing the boundaries of the instruments: so in the compositions for ensemble, as an example, you’ll not find the usual glissandi but notes mostly on the higher pitches.

I’ve written three reviews of old music – the two Xenakis CDs were released by Warner Classics in 2007 – because I wanted to recap a little the meaning and the practice of a music that nowadays is losing part of its how-to. As I wrote in the last multiple review, when I look around myself I mostly feel the struggling and the difficulties of a niche to be issued and to be heard by a larger audience, and the difficulties from the younger musicians to build a vision from an inner to an outer world. But since the world of rock and other contaminations has mostly completely gone, improvised music and the avant garde is still the most important tool to critique our society and imagine something better.

From September, other releases are waiting for us: from the new edition of Coltrane’s Blue Train with a disk of never heard before material, to a couple of new releases by the Japanese enfant terrible Keiji Haino, one with SUMAC. I hope to hear all of this stuff and more, but for the moment I wanna go back to the records I bought during these last years and share with you some hidden gems that maybe you have lost through the years. After all, music is a matter of love, and not a matter of being fashionable.