Having composed a little surrealistic poems myself and for myself, I can deeply understand that, even if our science is nowadays criticizing the idea of a ‘subconscious’ that psychoanalisis posed as angular rock of its exploration of the mind, there’s something hidden into ourselves that social life and rationality try sometimes to hide from our conscience. This hidden part is strictly related to our desires. I remember, as an example, that sensation of hunger and sexual desire I felt before I ended my first painting (horrible as it was, being my first attempt, but this is not the point). Gentle feelinga, not related to the phenomenon of craving as it happens to you when smoking a joint.

Obviously Sufi music is not related to desire, but if you read Rumi poems, being near to God is quite often comparted to be near a beautiful lover, or to being drunk from love. Sufi music, instead, is varied and you can find different kind of music with different kind of intent. Sufi music from Morocco, called Jbala, is a particular style whose goal is to induce into the listener, with performances during many days, a state of trance, in particular related to the loss of the sense of time.

The psychedelic qualities of the music of the Sufi from Joujouka hit for sure the first journalists that from the 1950s on started to testify their existance. At the same time, the following decade, the same qualities attracted both Brian Jones from The Rolling Stones and Beat poets like Paul Bowles, William S. Burrooughs and Bryon Gysin. After being introduced to the world by Jones himself who issued the album Brian Jones Presents the Pipes of Pan at Joujouka (1971) and their following collavoration with Ornette Coleman for the album Dancing In Your Head (1977), the group of musicians started to being recognized all around the world.

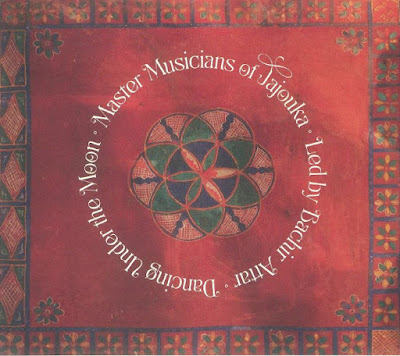

In fact, both contaminated themselves with the world of contemporary music: the “Joujouka” masters played with Jarvis Cocker and The Orb, while the “Jajouka” were produced at least in one of their albums by Bill Laswell. So in this post we’re gonna describe last album issued, this year, by the second combo, titled “Dancing Under The Moon”. Produced by Jacopo Andreini, drummer of the post punk Italian-French band L’Enfance Rouge (one of my favourite groups ever apart from jazz music), and featuring a booklet full of photos from the sessions and liner notes by the famous journalist Stephen Davis, author of books about Led Zeppelin and Jim Morrison, the album foresee sessions recorded on November 2019.

The band is comprised of seven members playing different instruments as ghaita (a double-reed flute), guinbri (a large plucked half-spike lute), lira (a crossbar lute) , violin, and different types of percussions. There are pieces of music where the percussions are widely spreaded as in Dancing In Your Mind, or where a sweet flute and the lutes introduce a crescendo as in The Bird Prays For Allah, and other where singing is on the foreground as in Yes, Yes, Be Patient My Heart. As I can understand through the titles of the pieces, the themes are the classic sufi themes: the love of God, the chant of love from nature, being ‘intoxicated’ or exalted by the love of God himself.

Don’t be surprised to read about such music in a blog related to jazz and improvised music. On one hand, these musicians played with a jazz master like Ornette Coleman in one of his most beautiful records, on the other hand this music deserves to be recognized since I truly believe that music can root all human beings into another dimension from where we can go back with new tools and skills in order to improve our world. You don’t need to believe in God for that, it is enough to look at the climate change and the war to get how much we need a new way of thinking.