My memory goes back to that time in which Sorey was an important part of Roscoe Mitchell’s various line-ups, and I was focused on that music, so deep and visceral but also cerebral and complex. At a certain point, I realized that what Roscoe was achieving was kind of a ‘zen’ music, where the research for a new self as an improviser was leaving place to the simple essence of being. I was curious of hearing Sorey playing with other musicians, to hear what he could realize with another dress.

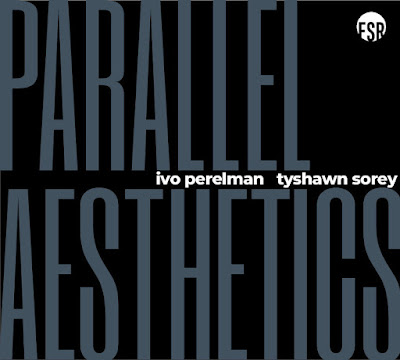

So, you can imagine how happy I was while I found out that Perelman sent to me, through my email address, the files of his new piece of art, this double album titled “Parallel Aesthetics”. I have no liner notes, no press release, only the music and the images on the cover. And that’s enough. After all, I am a person who writes about improvised music since 2010, so I’m supposed to be able to give life with words to something worth to accompany what my ears are listening to in this moment …

But let’s start with the basic facts: the double album is composed by a couple of records, the first including four compositions for a total time of 55 minutes, while the second features only two tracks for an amount of 37 minutes. Perelman is a musician that, after attending the Berklee School of music for only one semester, moved to L.A. where, three years after, he gave life to his first album, before moving to N.Y. His musical style is somewhere between the open but oblique singing of an Ornette Coleman and the edginess of a Steve Lacy, even if he concentrated himself on tenor saxophone and has a personal, distinct voice.

Sorey, who shared the stage with musicians as diverse but unique such as John Zorn, Muhal Richard Abrams, Anthony Braxton and Wadada Leo Smith, well known for his commitment both in the field of jazz and contemporary music, can be seen, as a pianist, as the missing link between Cecil Taylor and David Tudor – even if I know how much these two extremes are hard to put together – while on drums he perfectly fits into that tradition of musicians using percussions to give life to beautiful colours more than concentrated on marking the time.

What I can report for sure is that, once again, even if In the world of improvised music, at least in the purest world of intentions such kind of music has been played more and more, indeed while listening time stops, the miracle of a dialogue between two well refined musicians is happening as it happens while listening to the best albums you have in your collection if you are lucky or educated enough. I mean, you know that magic. Rational discussions about how this music is tracing a new line or is following a path, or anything in the middle, fade away in front of such mastery and enchantment.

But if there’s magic, for sure there is innovation. Sorey and Perelman with this albums are really giving life to an encounter between worlds and inspirations, and their ‘parallel aesthetics’, their attempt to create a dialogue between two worlds is really a new world in itself. There is intense flowing, moments of amazing exchanges, a vibrating feeling, some telluric and velvet sparks, but, most of all, I can clearly hear this sensation of listening to musicians which are telling something.

Because, even if you’ll pass through different temperatures and feelings, the final idea is that of a music where the concentrated and the relaxed are perfectly balanced. This means there is a magic equilibrium between the mind, the intention and the output of the musicians. And since it is difficult to reach such a result, I’m writing that this is possibly the best output for this year as far as improvised music/jazz music I’ll be able to listen to in 2025. Now, I’m curious to get back to this review and this release in December, and see if it has kept its promises.

.jpg)