Many months have passed since I wrote my last review. Many albums have seen my desk and my CD reader, or have been transferred to my laptop. The fact is, I’ve started writing for an Italian magazine online, in my native language, but after some months the articles were not published, nor rejected. They were simply frozen on the virtual desk. Then there was the theatre laboratory, and the arts academia. And my daily job.

But since

many musicians have sent to me their beautiful works, and since I have bought

some other records that to me were worth listening to, now I want to give my

reader a small “best of 2025”. So, I’ll start in no particular order. There

won’t be a podium, and the albums will not be displayed from worst to best or vice

versa. The reader is free to skim through the lines and read the reviews of the

albums he had listened to or maybe he’ll want to discover the music he was not

aware of.

As in the

past, you will find albums coming from Italy as much as from the rest of the

world, experimental records and noise rock, metal influenced by jazz and

industrial music. Obviously my (non-)ranking is subjective, so don’t mind if I

miss LPs or CDs you liked: it is impossible to be conscious of everything that

sorts out of the music business, and every time I read magazines, on line or on

paper, I see a beautiful anarchy coming out of them, more than a dreadful or

mortal order. That’s life!

Wadada Leo

Smith/Vijay Iyer “Defiant Life” (ECM)

Leo Smith’s

trumpet is interspersed with layers and layers of piano, Fender Rhodes and

electronics, but the music is always essential and the compositions are created

by subtraction. The dedications to Patrice Lumumba and Refaat Alareer (poet,

activist and co-founder of the project ‘We Are Not Numbers’ in Gaza) say it

all.

And so,

even if sometimes the (abstract) ‘muezzin call’ we are accustomed to listen

while hearing Wadada Leo Smith trumpet here is more elliptical than in his

usual concerts or records, the meditative atmosphere can bring consciousness

about the nature of activism – it doesn’t sort out of the will to affirm oneself,

but from a deep connection with the inner self and with reality: this is at

least what the music suggested to me.

Nine Inch

Nails “Tron: Ares” (The Null Corporation / Walt Disney / Interscope)

And even if

Reznor is assuring in 2026 we’ll see other new NIN material, this album in the

end, thanks to pieces like ‘As Alive as You Need Me to Be’, the duet with the

Spanish singer Judeline ‘Who Wants to Live Forever’, the meditative ‘I Know You

Can Feel It’, and a bunch of

instrumental tracks like the ecstatic ‘Echoes’ or the threatening ‘Infiltrator’

are raising high the flag of the band name. Obviously, we will be grateful to

Reznor and Atticus Ross for the new

material we’ll hear this year, with great curiosity.

Swans

“Birthing” (Young God)

The

perfection of tracks like ‘The Merge’, with his noisy introduction and his

circular, even if a little limping, rhythms, make us forget about Gira

pretending “The Beggar” to be the testament of The Swans (do you remember ‘Michael

Is Done’?) and the following tour as the last of his career. It is not the

first time this happens with him, but the beauty of the music makes me curious about

the announced new phase of Gira’s creature as I was curious about his pupil

Devendra Banhart when his first albums came to light.

Model/Actriz

“Pirouette” (True Panther Sounds)

But also

‘Diva’, with his static tension, the second single from the album, has some

intriguing quality – as the rest of the album – as if the music were able to

bring the listener on the edge of the chasm leaving him here to dance. “I won’t

leave as I came” sings Haden, and this is exactly the destiny of the listener

of this album: the music and its meaning will remain glued to your conscience,

and it will be a beautiful experience.

KnCurrent “self

titled” (Deep Dish)

Each track

has its own peculiarities and particular sound/vision in it, and the instruments

involved and the techniques they speak are so different from one piece of music to the other, but taken as a

whole the album is showing how much the old masters of improvised music are far

from been merely legends of the past and can leave tracks into the present.

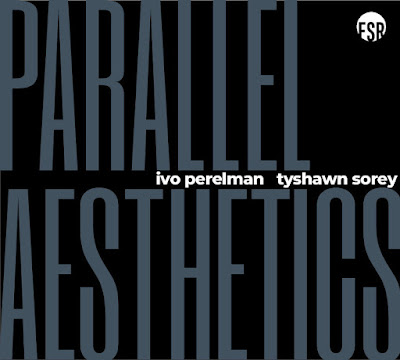

Another album I wrote a review early this year, musically different but

genuinely beautiful, is the album “Parallel

Aesthetics” by Ivo Perelman and Tyshan Sorey: my advice is to enjoy it in

its full length if you still miss it.

Robertson/Dell/Ramond/Klugel

“Blue Transient” (Nemu)

An intimate

and intriguing journey through the depths of sounds and the visions of these

musicians. Sometimes when I listen to them I ask myself why they’re not put on

the flag by every blog/website/magazine related to experimental music. This is

not nostalgia or carbon copy; this is devotion to an idea of music full of

personal nuances and will to create.

Duck Baker “There’s

No Time Like The Past” (Fulica)

Far from the

deconstructions of musicians like Marc Ribot and Derek Bailey, Baker is one of

the many, too many good underappreciated artisans that silently but with great

love and devotion are leaving us an opus of beauty and truth. This album is a

testimony of how a someone able to create a music rooted into tradition can be

taken as example for other musicians or simple listeners as far as breadth of intention

and clarity of vision.

Tropical

Fuck Storm “Fairyland Codex” (Fire)

If you find

difficult to think of this genre as self-renovating again after last year “Romance”

by Fontaines D.C., this album will definitely change your mind. Drums, drum

machines, synths, pedal steel guitars are creating for the listener a wider

landscape, full of the irony and the abrasiveness that is typical of this style

of music. But the creative spark is here to stay, and I think many of you will

get back to this album also in 2026 …

Messa “The Spin”

(Metal Blade)

Messa are

an Italian band (from the suburbs of Treviso if I remember well) who loves to

mix doom metal with jazz guitar licks and harmonies. But the result is different

from a pure melting pot of different styles: in a way only at an attentive

listening you’ll find the single elements melting together. Because the effect

is that of a perfect blend. A small miracle from my country, Messa are a band

worth seeing in live concerts and spanning through its career in order to enjoy

its evolution.

Marc Ribot “Map

Of A Blue City” (New West)

Ribot and

his pals give life to a music that can be put aside of the beautiful folk of people

like Nick Drake, but with a tinge of contemporary electric experimentations and

some Latin nuances (see ‘Daddy’s Trip To Brazil’). There’s also space to put

into music a poem by Allen Ginsberg (‘Sometime Jailhouse Blues’). One of the

major works of Ribot to me, along with Spiritual Unity (with Ribot recreating

with his guitar the music of Albert Ayler) and the famous (for the wrong

reasons) ‘fake-cuban’ albums.

Suede “Antidepressants”

(BMG)

Symmetrical

to last year’s The Cure comeback, and different from the poorly written (in my

opinion) Lebanon Hanover’s “Asylum Lullabies”, this record, released by a major

label, has new obscure nuances the old Suede were completely missing. And if

the album’s cover is inspired by a famous Francis Bacon (the painter) photograph,

the music is more essential and plainer than in the past.

So, these

are the album I enjoyed this year – along with older stuff – and these are my

advices after almost a year of silence with this blog. I don’t know honestly

how much I will write this year 2026. But obviously I’ll keep on listening new

music, and so get ready for new releases like the new album by Wadada Leo Smith

and Ivo Perelman. I still need to listen to this unprecedented collaboration,

but I hope it will be a good sign for all the new alternative and experimental

music that will be released this year.

.jpg)